Our contributor @DaemonOrtega delivers a sharp take on enlargement, calling for substantial reform as the current process fuels institutional fatigue and leaves a vacuum for hostile actors to fill.

Brief Content

The Ave Europa Team warmly thanks our member @DaemonOrtega for his outstanding contribution to our plenary coverage.

This brief breaks-down the content of the original 2024 Commission reports for both Montenegro and Moldova, as well as the subsequent Parliamentary committee reports and amendments. It includes a summary of each political group’s amendments and which MEPs were most active in tabling them. The brief ends with a reflection on the EU’s enlargement strategy and its shortfalls.

The Commission’s cautious optimism no longer matches the reality on the ground. As our contributor Daemon Ortega sharply notes, today’s enlargement strategy has become a bureaucratic endurance test—one that breeds institutional fatigue, fuels frustration among candidate countries, and opens dangerous geopolitical vacuums.

Montenegro’s case is telling: more than a decade of negotiations, only 6 chapters provisionally closed. Meanwhile, strategic rivals like China and Russia step in where EU promises stall.

If the Union wants to uphold its geopolitical credibility and deliver on its historic mission of peace and stability, enlargement must be treated not as a checklist—but as a strategic imperative. The pace, the tools, and the mindset must change.

Background of Union Accession

The European Union enlargement process represents one of the Union’s most significant foreign policy instruments, serving as a mechanism for extending European values of democracy, rule of law, and human rights beyond the Union’s frontier. The current legal framework governing EU accession is the ‘Copenhagen criteria’, adopted in 1993, which establishes the fundamental conditions candidate countries must fullfil to achieve membership.

The accession process operates through a structured negotiation framework comprising 35 Chapters of the EU Community acquis, including items ranging from free movement of goods, to science and research, to external relations, and more. These are typically bundled into six thematic clusters to keep relevant Chapters better organised, and to help determine the overall pace of negotiations:

(1) fundamentals; (2) internal market; (3) competitiveness and inclusive growth; (4) green agenda and sustainable connectivity; (5) resources, agriculture, and cohesion; and (6) external relations. Each individual Chapter requires meeting opening benchmarks before negotiations begin and closing benchmarks for provisional closure1, with final closure occurring only upon full compliance verification2.

Central to the current enlargement methodology is an emphasis on the ‘Fundamentals’ cluster, consisting of Chapters 23 (Judiciary and Fundamental Rights) and 24 (Justice, Freedom, and Security). These encompass judicial independence, anti-corruption frameworks, fundamental rights protections, border management, asylum systems, and migration policy. These chapters require meeting interim benchmarks throughout the process, with sustained implementation verified through regular assessment reports like the ones discussed in this brief for Moldova and Montenegro.

Accession processes typically span 10–15 years from initial application to membership. Montenegro and Moldova represent distinct cases, however, with Montenegro having received candidate status in 2010 and opened accession negotiations in 2012, and since advancing the most compared to other Balkan candidates. Of the two, Montenegro has advanced the furthest, with all Chapters opened and six provisionally closed.

Moldova’s trajectory is far more recent, sparked by the renewed enlargement momentum following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It was granted candidate status that same year together with Ukraine, and began accession negotiations in June 2024, reinforced by a constitutional referendum later in October 2024 to determine popular support for EU membership despite significant Russian interference campaigns.

Both the Commission and Parliament play a role in monitoring accession progress through annual country reports and resolutions, which provide democratic oversight of the enlargement process. Dissecting these most recent documents will be the subject of this Enlargement Brief.

Analysis: Montenegro

Commission’s 2024 Assessment: Mixed Progress

The European Commission’s 2024 report on Montenegro found it was in fulfillment of interim benchmarks for Chapters 23 and 24, marking a crucial milestone for the ‘Fundamentals’ cluster. However, the Commission also identified persistent challenges across democratic institutions.

On electoral reform, the assessment was particularly critical, noting that the “majority of pending OSCE/ODIHR recommendations have not been addressed” and that the legal framework “requires comprehensive reform”. The Commission emphasised that while Parliament can “exercise its powers in a mostly satisfactory way”, political tensions and “inter-ethnic polarisation has resurfaced”, undermining political stability.

In public administration, Montenegro received a “moderately prepared” rating with “limited progress”, highlighting weaknesses in budget transparency (scoring 48/100 in the Open Budget Survey) and concerning gender parity trends in public employment. The Commission noted particular problems with commitment control in the accounting system and lack of accounting standards.

That being said, the report also acknowledged “good progress” in combatting organised crime and managing migration/asylum, while relations with neighbours remained generally stable, though Chapter 31 (Foreign, Security, & Defence Policy) negotiations stalled due to Croatian objections over unresolved bilateral issues.

Parliament’s Draft Response: Cautious Optimism

Rapporteur Marjan Šarec (Renew Europe)’s initial draft report in February 2025 largely aligned with the Commission’s findings, welcoming Montenegro’s meeting of interim benchmarks for Chapters 23–24 and closure of three additional negotiating Chapters, bringing the total to six provisionally closed.

The draft did, however, express concern about “political boycotts and blockades” and “re-emerging tensions and ethnic polarisation”, echoing Commission warnings about political stability. Parliament’s draft called for comprehensive electoral reform, noting the need to “fully align its electoral legal framework with EU standards” and implement OSCE/ODIHR recommendations.

Regarding bilateral relations, Parliament noted regret that Chapter 31 could not be closed in December 2024 due to outstanding issues with Croatia, while emphasising that “using unresolved bilateral and regional disputes to block candidate countries’ accession processes should be avoided”.

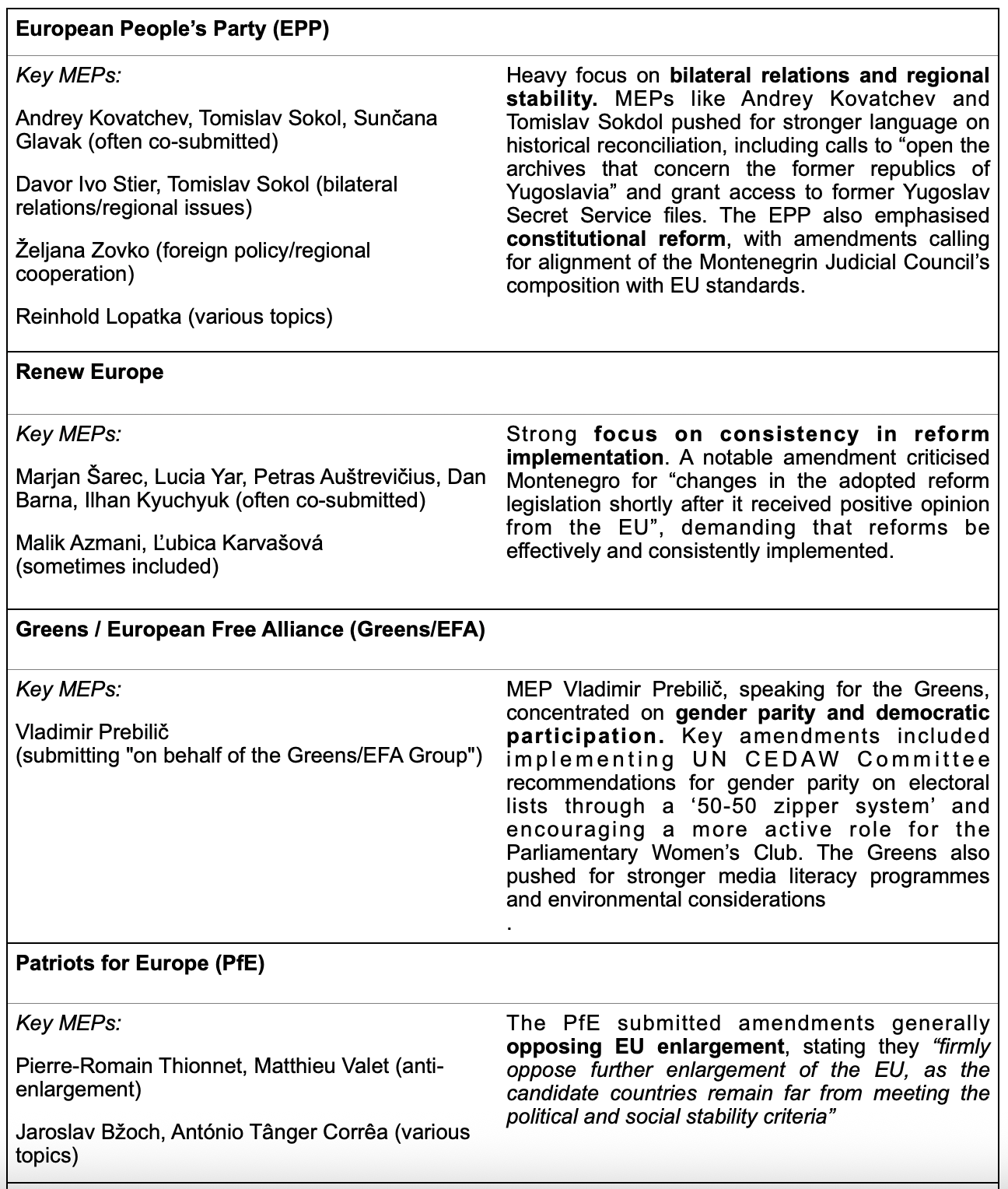

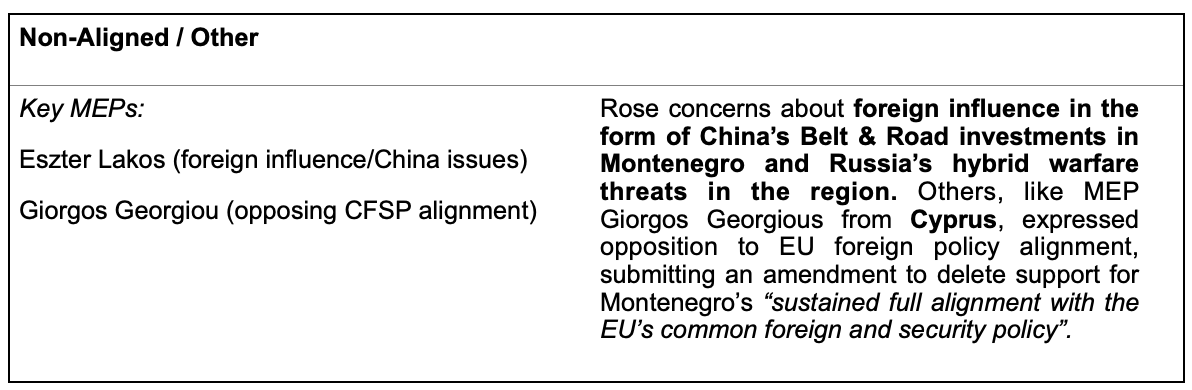

Parliamentary Amendments

The amendment process in March 2025 included 235 amendments tabled by various political groups.

Final Committee Report: Mainstream Consensus

The final committee report in May 2025 reflected an amalgamation of mainstream political group positions, adopted with strong cross-party support: 51 votes in favour (EPP, S&D, Renew, Greens/EFA, The Left, and ECR), 7 against (mainly PfE and non-aligned), and 7 abstentions.

The final text maintained Parliament’s support for Montenegro’s future EU membership while incorporating several key amendments. It added specific warnings about “malign foreign influence, disinformation campaigns, and other forms of influence, including election meddling, hybrid warfare strategies, and unfavourable investments from non-EU actors, particularly Russia and China”.

The report addressed citizenship law concerns, expressing worry about attempts to amend the law on Montenegrin citizenship which “could have serious long-term implications for the country’s decision-making processes and identity”. It emphasised the need for broad societal consensus and consultation with the EU on citizenship changes.

Lastly, on bilateral relations the report struck a balanced tone, acknowledging Croatian concerns while calling for constructive solutions. It welcomed consultations between Croatia and Montenegro to iron-out these issues, yet maintained that bilateral disputes should not block accession processes.

Analysis: Moldova

Commission’s 2024 Assessment: Resilience Amid Challenges

The Commission’s 2024 report painted a picture of a country demonstrating resilience despite unprecedented challenges in the form of Russia’s war in Ukraine and intensified interference campaigns targeting Moldovan democracy. The report noted that Moldova had “continued to progress on the path to EU accession”, yet also highlighted significant structural challenges which require attention.

On democratic institutions, they found that Moldova’s Parliament operates within a “broadly enabling environment” for civil society, yet noted concerns about the abrupt dismissal of the National Bank of Moldova governor in 2023, which “raised some concerns about good governance”. The electoral framework received mixed reviews, with the Commission acknowledging the new Electoral Code while noting it had been amended three times since its entry into force, including less than a year before elections.

On the economic criteria Moldova received ratings of “between an early stage of preparation and having some level of preparation” for both functioning market economy indicators and capacity to cope with competitiveness pressures. The Commission highlighted that major structural challenges remain, including “high levels of undeclared work and weak rule of law”, while noting positive steps in public investment management and banking sector stability.

Parliament’s Draft Response: Cautious Support

Rapporteur Sven Mikser (S&D)’s draft report in March 2025 struck a carefully balanced tone, welcoming Moldova’s constitutional referendum results while acknowledging the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the democratic process. It emphasised that both the constitutional referendum and presidential election “confirmed the support of a majority of the Moldovan people for the country’s goal of EU membership”, despite the Russian interference campaign.

The draft report welcomed the Commission’s Moldova Growth Plan and its €1.9 billion Reform & Growth Facility. Parliament’s initial response stressed the importance of clear communication and combating false narratives about the EU and its policies, to highlight the short- and long-term benefits of EU accession.

That being said, the report also reflected concerns about Moldova’s institutional capacity. It noted that despite attempts to reform the judicial system, it remains vulnerable to manipulation. Parliament emphasised that meaningful civil society involvement would be crucial in strengthening trust in democratic institutions to boost public support for EU accession-related reforms.

Parliamentary Amendments

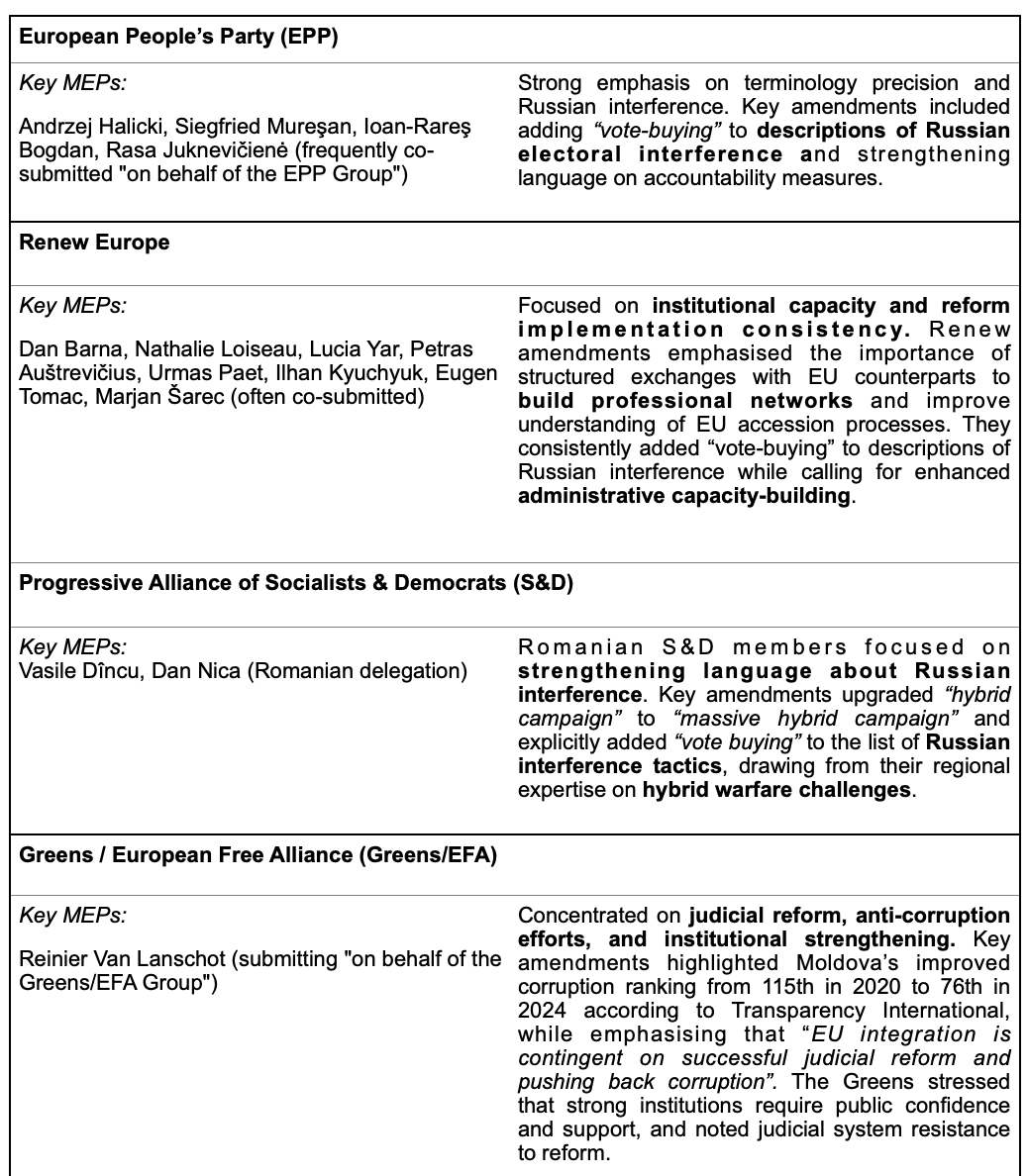

The amendment process in April 2025 included over 180 amendments tabled by various political groups.

Final Committee Report: Mainstream Consensus

The final committee report in May 2025 was adopted, like with that of Montenegro, with cross-party support: 52 votes in favour, 11 against, and 3 abstentions. This strong majority reflected mainstream European support for Moldova’s EU membership despite the challenging security environment. Pro-enlargement forces (EPP, S&D, Renew, Greens/EFA, The Left, and most ECR) formed the majority, while opposition was mainly from PfE, ESN, and some non-aligned members.

The final text incorporated key amendments from across the political groups, resulting in a document that strengthened language about Russian interference and acknowledged Moldova’s progress, particularly its improved governance indicators and corruption ranking from Transparency International. However, it also underscored the difficulties in reforming Moldova’s judiciary and its vulnerability to manipulation.

On economic integration, the report welcomed the Moldova Growth Plan while stressing the need for continued implementation of the Reform Agenda. It stressed the importance of civil society engagement and communication to maintain public support for EU accession reforms.

Conclusions

The European Commission’s assessments of Montenegro and Moldova reflect a familiar pattern in EU enlargement policy: comprehensive technical evaluation coupled with cautious optimism about progress. This position aligns closely with the Commission’s traditional approach to candidate countries, one welcoming and encouraging of integration while maintaining rigorous standards of accession. However, this strategy has inadvertently led to glacial progress, dwindling patience, and a look for alternatives.

Montenegro’s case is particularly illustrative of the challenges with the current enlargement framework. Despite receiving candidate status in 2010 and opening negotiations in 2012, the country has spent over a decade navigating the accession process with only 6 of 35 Chapters (provisionally) closed. This protracted timeline raises fundamental questions about the effectiveness of current enlargement methodology, especially when contrasted with the Eastern Expansion that followed the Soviet Union’s collapse. The countries of Central and Eastern Europe — many facing comparable governance challenges — completed their accession processes in significantly shorter timeframes and under demonstrably less stringent conditions.

This disparity in standards and pace creates not merely a perception of unfairness, but tangible geopolitical consequences that threaten European strategic interests. The prolonged uncertainty surrounding Balkan accession has created a vacuum that external actors have been eager to fill. China’s Belt & Road Initiative found fertile ground in a region where EU promises of integration remain perpetually out of reach.

The Union’s reluctance to match its rhetoric of support with concrete, timely action has created space for competitors to advance their influence in what should be Europe’s natural sphere of integration. When EU Member States express surprise at candidate countries’ willingness to engage with Chinese or Russian initiatives in exchange for much-needed investment, they reveal a troubling disconnect between policy expectations and delivery.

For the Union to fulfil its enlargement commitments and secure its strategic interests in the Western Balkans, fundamental reform of both pace and approach is essential. This requires moving beyond the current framework of integration as a bureaucratic endurance test, and toward a more dynamic model that rewards genuine progress with concrete integration steps.

More critically, it demands that the EU begin to think of enlargement not merely as a technical process, but as an urgent strategic imperative to deliver the Union’s raison d’être: peace, stability, and prosperity.

When the candidate country meets technical requirements and has implemented necessary legislation, yet Chapters remain subject to monitoring and can be reopened if compliance deteriorates.

When the EU confirms sustained implementation and overall readiness for membership obligations.